Introduction:

This is not the first time. Not even second in US

This is not only about semiconductor chips, but the United States has lost cameras, light bulbs, televisions, hard disks, displays, silicon chips, among others to other countries when it came to scale them up to products.

The dynamics of semiconductor economics have contributed to the challenges faced by high-performing American companies in the race of incremental innovation and reinvention. As a result, the U.S.has experienced a decline in its innovative output.

What all has America lost to the world despite inventing them first

Light bulb to Japan:

The light bulb was originally brought to life by America’s own Thomas Alva Edison. This creation marked the initiation of a surge in electricity consumption at the turn of the 20th century, propelling the rise of General Electric (GE) in the United States. For nearly a century, GE led the global arena of lighting and power.

The 1960s witnessed the involvement of American corporations, research institutions, and universities in the practical development of LED devices.

Key contributions came from renowned entities like GE, RCA, Texas Instruments, IBM, MIT Lincoln Laboratory, and Bell Labs. Similar to the evolutionary pattern of other semiconductor devices, LEDs began in rudimentary forms, hindered by costly manufacturing.

In 1968, visible and infrared LEDs carried a staggering price tag of $200 per unit, greatly limiting their practicality. Consequently, despite considerable research and inventive efforts, American companies struggled to effectively harness their innovative capabilities.

The high expenses coupled with limited utility resulted in American firms largely sidelining LED technology. However, the late 1980s witnessed a turning point when a modest Japanese company named Nichia Corporation took up the mantle. Nichia embarked on research and development initiatives aimed at surmounting a significant barrier—developing a robust blue LED.

These endeavors culminated in a Nobel Prize-winning scientific breakthrough: the creation of a flawless blue LED employing gallium nitride (GaN). As a result, Nichia achieved a breakthrough by innovating white and brilliant LED light bulbs.

These semiconductor-based bulbs outshone Edison’s incandescent bulbs in energy efficiency, rendering the latter wasteful, dissipating up to 85% of energy. This transformation propelled LED light bulbs to swiftly emerge as a superior alternative, setting in motion the forces of creative destruction that challenged America’s dominance in light bulb manufacturing.

Hence, the decline in America’s leadership in the light bulb invention domain cannot be attributed to merely low-cost labor or intellectual property violations.

Rather, it was the outcome of intricate semiconductor economics that led American enterprises to make choices that eventually culminated in relinquishing their hold on this inventive realm.

Read more: How Japan Beat the US in the First Chip War

Radio & Television to Sony, Japan

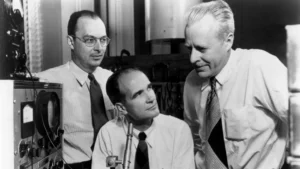

Back in 1929, the commercial radio sector had flourished into a billion-dollar industry, with American companies like RCA leading the way. However, with the groundbreaking invention of the Transistor in 1947, the United States experienced a shift in the manufacturing dominance of radios to Japan.

Throughout the 1960s, America’s reliance on imported radios steadily increased, ultimately leading to the decline of RCA’s radio manufacturing business.

Surprisingly, it was Sony that pioneered the reinvention of the radio by fundamentally altering the technology core from vacuum tubes. It’s worth noting that Sony wasn’t the first to attempt this feat.

Prior to Sony’s endeavors, American companies like RCA and Texas Instruments had ventured into similar territory. However, these American attempts faltered as the Transistor radio emerged in a less advanced state.

In contrast, Sony remained committed to refining the transistor technology, capitalizing on the principles of semiconductor economics. In a short span, Sony managed to outpace RCA’s vacuum tube-based technology, producing transistor radios that were not only superior but also more cost-effective.

As a result, the United States ceded its position in radio manufacturing to Japan. This trend echoed across other consumer electronics sectors, such as television, VCRs, and audio recording, where America’s competitive edge gradually eroded.

Also Read: How Sony Turned a War-Torn Japan into the King of Electronics

Memory chips to Toshiba, Japan

In 1957, IBM introduced a groundbreaking invention: a hard disk with a capacity of 5MB, weighing a substantial one ton. Nearly two decades later, Toshiba entered the hard disk manufacturing arena.

However, Toshiba swiftly ascended to global leadership in this field due to its adeptness in incremental innovation, ultimately prompting IBM’s exit from the hard disk market. The semiconductor industry’s advancements, particularly in lithography that facilitated the shrinking of read-write heads, significantly contributed to the evolution of hard disk technology.

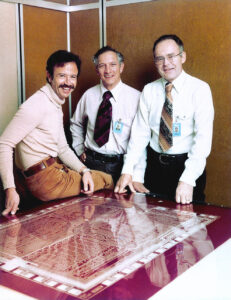

Toshiba’s pivotal contribution followed in the form of NAND flash memory innovation. Interestingly, the origins of this breakthrough could be traced back to the invention of floating-gate MOSFET (FGMOS) technology at Bell Labs in 1967.

Similar to the developmental trajectory of other semiconductor devices, this technology had initial limitations, manifesting as sluggish performance and complex manufacturing processes. Consequently, American firms predominantly directed their early floating-gate memory efforts, such as EPROM and EEPROM, toward specialized military applications during the 1970s.

However, it was the inventive endeavors of Fujio Masuoka, during his tenure at Toshiba, that steered the course toward an entirely novel data storage solution: NAND Flash memory. This development further chipped away at America’s data storage industry, weakening its position in the global market.

Read more: Who invented memory..Intel or Toshiba?

Loss of camera to Sony, Japan

In September 1888, George Eastman secured a patent for his box-type camera, and subsequently, on May 23, 1892, along with Henry A. Strong, founded Kodak. Over the course of a century, Kodak achieved global recognition for its innovation by progressively enhancing film, chemicals, and cameras.

However, the strategic application of semiconductor economics by the Japanese company Sony eventually led to the downfall of this renowned American enterprise.

In 1969, Bell Labs introduced the 8×8 Charge-Coupled Device (CCD), an electronic image sensor. Unlike traditional film, CCD harnessed electrons in response to photons, capturing images pixel by pixel electronically, without the need for extensive processing time.

Read More:Follow us on Linkedin for all major updates

After Innovation

This innovation posed a potential alternative to Kodak’s film-based approach. Although the concept emerged in rudimentary 8×8 image sensors, far from the over 2 million pixels found in standard photographs, Sony recognized its latent promise.

Sony dedicated substantial research and development resources to cultivate this untapped potential. In contrast, when Kodak created the first digital camera in 1974, its management decided against further pursuit.

The initial digital camera, engineered by Kodak’s Steven Sasson, weighed 8 pounds (3.6 kg) and boasted a mere 100 × 100 resolution (equivalent to 0.01 megapixels). This limited capability failed to convince Kodak’s leadership of its commercial viability.

Yet, the latent power of semiconductor economics would prove Kodak’s judgment wrong in the 1990s. Sony’s persistent efforts culminated in the development of high-quality CMOS image sensors, which paved the way for digital cameras.

The continuous improvement in quality and reduction in manufacturing costs propelled digital cameras into the forefront, acting as a force of creative destruction against film-based cameras. As a result, the epicenter of camera innovation transitioned from America to Japan.

Conclusion:

Undoubtedly, the United States has been the originator of numerous remarkable technologies, fostering innovation and generating pioneering products. However, regardless of their initial significance, these innovations often emerged in rudimentary forms.

To realize their full potential in terms of generating wealth and establishing markets, a continuous stream of ideas for incremental enhancement and reinvention was essential. This process naturally facilitated their movement across the boundaries of different companies and nations, resulting in an inherent inclination for inventions to migrate.

As elucidated, the evolutionary and migratory trajectory applies universally to inventions, regardless of their magnitude. Many variables contribute to this phenomenon, but a key driver lies in the intricate decision-making challenges.

Particularly influenced by semiconductor economics, American innovators have grappled with profound dilemmas in this regard. Consequently, despite pioneering these innovations and initially leading in both innovation and market establishment, the United States has witnessed the erosion of its supremacy in numerous significant inventions.